If  is a transitive model of

is a transitive model of  , then either

, then either  admits a strongly amenable iterated truth predicate of length

admits a strongly amenable iterated truth predicate of length  or else there is a unique

or else there is a unique  so that

so that  admits a strongly amenable iterated truth predicate of length

admits a strongly amenable iterated truth predicate of length  but not one of length

but not one of length  . (We can go beyond

. (We can go beyond  , but this starts getting into subtleties I want to avoid in a paragraph introducing another topic.) However, if

, but this starts getting into subtleties I want to avoid in a paragraph introducing another topic.) However, if  has ill-founded

has ill-founded  , this is no longer the case. We can find different full satisfaction classes for

, this is no longer the case. We can find different full satisfaction classes for  which can be iterated different lengths. Indeed, any reasonable length is possible.

which can be iterated different lengths. Indeed, any reasonable length is possible.

In my previous post, I gave an application of iterated truth predicates. The only structures dealt with there were transitive. In a transitive world, things are simple. It is easy to check that the truth predicate for a structure is unique. Since transitive structures have the correct  , they are correct about what formulae are. Thus, the only class which can be added to a transitive structure which looks like its truth predicate is its actual truth predicate.

, they are correct about what formulae are. Thus, the only class which can be added to a transitive structure which looks like its truth predicate is its actual truth predicate.

For nonstandard structures, things are not so nice. If we want to be able to use a class  for much, then we want the expanded structure

for much, then we want the expanded structure  to satisfy the axiom schemata of our theory—Separation and Collection for set theory, Induction for arithmetic—with a predicate symbol added for the class. When this happens, we say that

to satisfy the axiom schemata of our theory—Separation and Collection for set theory, Induction for arithmetic—with a predicate symbol added for the class. When this happens, we say that  is, in the case of set theory, strongly amenable or, in the case of arithmetic, inductive.

is, in the case of set theory, strongly amenable or, in the case of arithmetic, inductive.

Hereon, I’ll focus on models of arithmetic, but similar things can be said about models of set theory.

It’s easy to see that the actual truth predicate, which consists only of standard-length formulae, for a nonstandard model can never be inductive. Otherwise, apply the instance of induction for the property “there is a  -formula in the truth predicate”, which is true for

-formula in the truth predicate”, which is true for  and closed under successor, to get that the model must be the standard model, a contradiction. As such, if we want to do much we need something that looks like a truth predicate but includes formulae of all length, even nonstandard length.

and closed under successor, to get that the model must be the standard model, a contradiction. As such, if we want to do much we need something that looks like a truth predicate but includes formulae of all length, even nonstandard length.

The notion used by model theorists of arithmetic is that of a full satisfaction class. A satisfaction class for a model  is a class which satisfies the recursive Tarskian definition of truth. For instance,

is a class which satisfies the recursive Tarskian definition of truth. For instance,  is in the satisfaction class only if there is

is in the satisfaction class only if there is  so that

so that  is in the satisfaction class. It is full when it decides every formula, i.e. either

is in the satisfaction class. It is full when it decides every formula, i.e. either  is in the satisfaction class or else

is in the satisfaction class or else  is in, even for nonstandard

is in, even for nonstandard  .

.

Full satisfaction classes are well studied; see, for example, this survey article by Kotlarski. One important fact is that if a model admits a full satisfaction class (even a non-inductive one) then it must be recursively saturated. If the model is countable, then the converse also holds.

Another important fact is that full satisfaction classes are far from satisfying the uniqueness property from the standard world; Krajewski constructed countable models of arithmetic with continuum many different full satisfaction classes. Even if we restrict to inductive full satisfaction classes, things are no better. We cannot even guarantee that different full satisfaction classes give the same theory in the expanded language.

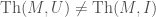

Proposition: There is  and

and  inductive full satisfaction classes so that

inductive full satisfaction classes so that  .

.

(I do not know who first observed this fact. I learned of it from Joel David Hamkins. In a joint paper with Ruizhi Yang he attributes a stronger form of this proposition to Jim Schmerl—see page 30. It is more-or-less his argument I now sketch.)

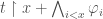

Proof sketch: Consider the theory  consisting of

consisting of  plus the assertion, formalized as an axiom schema, that

plus the assertion, formalized as an axiom schema, that  is an inductive full satisfaction class. (To be clear, the language for this theory is the language of arithmetic augmented with an extra predicate symbol for

is an inductive full satisfaction class. (To be clear, the language for this theory is the language of arithmetic augmented with an extra predicate symbol for  .) While the reduct of this theory to the language of arithmetic is complete,

.) While the reduct of this theory to the language of arithmetic is complete,  is not itself complete. This is just a version of Tarski’s theorem on the undefinability of truth. Now let

is not itself complete. This is just a version of Tarski’s theorem on the undefinability of truth. Now let  and

and  be two consistent but incompatible extensions of

be two consistent but incompatible extensions of  . By a standard resplendency argument, find a model

. By a standard resplendency argument, find a model  and

and  so that

so that  and

and  . ∎

. ∎

It must be that  and

and  agree about standard formulae. Specifically, restricted to standard formulae they are both

agree about standard formulae. Specifically, restricted to standard formulae they are both  . Their disagreement can only occur for nonstandard formulae—

. Their disagreement can only occur for nonstandard formulae— may think that nonstandard

may think that nonstandard  is true while

is true while  know better and think that

know better and think that  is false.

is false.

The above proposition shows, however, that if we are interested not in truth but rather in truth about truth then disagreement can happen at a standard level. Any full satisfaction class for the structure  must have

must have  as an initial segment. As such, if we want inductive iterated full satisfaction classes starting with

as an initial segment. As such, if we want inductive iterated full satisfaction classes starting with  and

and  —say we only want to iterate one step to get

—say we only want to iterate one step to get  and

and  respectively—then there is no longer any guarantee that they line up if we restrict to looking only at standard truths.

respectively—then there is no longer any guarantee that they line up if we restrict to looking only at standard truths.

We have no hope that the theory we get from iterating truth is independent of our choice of satisfaction class, but perhaps we can find other invariants. In my previous post, I showed how to construct transitive models of set theory which admit a strongly amenable iterated truth predicate of length  but one of length

but one of length  . As we’ve seen, for nonstandard models we have a choice of satisfaction class. But we might hope that how far out we can iterate a satisfaction class (where we have to make a choice at each level how to proceed) is an invariant.

. As we’ve seen, for nonstandard models we have a choice of satisfaction class. But we might hope that how far out we can iterate a satisfaction class (where we have to make a choice at each level how to proceed) is an invariant.

Put differently, we can think of the inductive iterated satisfaction classes as forming a tree. The root is simply the empty set. Given a node in the tree, i.e. an iterated inductive full satisfaction class  of length

of length  , its children are all the

, its children are all the  -iterated inductive full satisfaction classes which extend

-iterated inductive full satisfaction classes which extend  . Is it the case that all branches through this tree have the same length?

. Is it the case that all branches through this tree have the same length?

The answer is no.

Before seeing why, let’s fix some notation. Let  be the theory consisting of the axioms of

be the theory consisting of the axioms of  plus the assertions that

plus the assertions that  is an inductive full satisfaction class. (This theory is in the language of arithmetic augmented with a symbol for

is an inductive full satisfaction class. (This theory is in the language of arithmetic augmented with a symbol for  .) Note that this theory is computably enumerable; it is a single sentence to say that

.) Note that this theory is computably enumerable; it is a single sentence to say that  is a full satisfaction class and a computable schema to say that

is a full satisfaction class and a computable schema to say that  is inductive. (

is inductive. ( stands for “compositional truth”; cf. this SEP article.)

stands for “compositional truth”; cf. this SEP article.)

Next, let  be all theorems of

be all theorems of  which are in the language of arithmetic. That is,

which are in the language of arithmetic. That is,  consists of all theorems of

consists of all theorems of  which don’t make reference to truth. It is not hard to see that

which don’t make reference to truth. It is not hard to see that  is a proper extension of

is a proper extension of  . For instance,

. For instance,  is a theorem of

is a theorem of  but, by a famous theorem of Gödel, is not a theorem of

but, by a famous theorem of Gödel, is not a theorem of  .

.

As a warm-up, let’s prove the following.

Proposition: Let  be countable and recursively saturated. Then, there is

be countable and recursively saturated. Then, there is  so that

so that  . Moreover,

. Moreover,  can be chosen so that

can be chosen so that  is also recursively saturated.

is also recursively saturated.

In informal language, the only thing that could possibly stop a countable, recursively saturated model from admitting an inductive full satisfaction class is its theory.

Proof: This is a standard argument by resplendency. For the sake of the reader unfamiliar with this kind of argument (and because I’d feel a little silly giving a one sentence argument :/) I’ll provide a more detailed argument.

The first step is to note that  contains nonstandard

contains nonstandard  which codes the theory of

which codes the theory of  . This is a fun exercise in writing down the correct recursive type. Next, let

. This is a fun exercise in writing down the correct recursive type. Next, let  be an effective enumeration of the theorems of

be an effective enumeration of the theorems of  . Finally, let

. Finally, let  be the formula expressing

be the formula expressing  , where

, where  is

is  .

.

Observe that  for all standard

for all standard  . By overspill, we can pick nonstandard

. By overspill, we can pick nonstandard  so that

so that  . Working inside

. Working inside  , apply the arithmetized completeness theorem to

, apply the arithmetized completeness theorem to  . This gives a definable class of

. This gives a definable class of  which codes a model

which codes a model  of

of  . (Of course,

. (Of course,  is an ersatz theory which consists of real, standard formulae as well as nonstandard formulae, so the preceding sentence is a bit of nonsense. What is really meant is that

is an ersatz theory which consists of real, standard formulae as well as nonstandard formulae, so the preceding sentence is a bit of nonsense. What is really meant is that  has a definable class which codes what it thinks is the satisfaction predicate of

has a definable class which codes what it thinks is the satisfaction predicate of  and that this satisfaction predicate includes

and that this satisfaction predicate includes  .) Restricting to the standard formulae, we get that

.) Restricting to the standard formulae, we get that  .

.

Further, we get that  end-extends

end-extends  . This is because

. This is because  thinks it is the standard model and that it embeds into any model of arithmetic. This is sufficiently absolute that if

thinks it is the standard model and that it embeds into any model of arithmetic. This is sufficiently absolute that if  thinks it then it really is true. As a consequence, we get that

thinks it then it really is true. As a consequence, we get that  and

and  have the same standard system. But then,

have the same standard system. But then,  and

and  are isomorphic. (This is a consequence of the more general fact that countable recursively saturated

are isomorphic. (This is a consequence of the more general fact that countable recursively saturated  are isomorphic if they have the same theory and the same standard system.) Letting

are isomorphic if they have the same theory and the same standard system.) Letting  be the image of

be the image of  under the isomorphism we get that

under the isomorphism we get that  , as desired.

, as desired.

The “moreover” part of the proposition is because for countable models, recursive saturation implies resplendency implies chronic resplendency. ∎

Similar to the definitions of  and

and  , we can define

, we can define  and

and  for truth about truth instead of just truth. That is,

for truth about truth instead of just truth. That is,  consists of

consists of  plus the assertions that

plus the assertions that  is a

is a  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class while

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class while  consists of the theorems of

consists of the theorems of  in the language of arithmetic.

in the language of arithmetic.

Proposition: Suppose  is countable and recursively saturated. Then, there are

is countable and recursively saturated. Then, there are  inductive full satisfaction classes so that

inductive full satisfaction classes so that  can be iterated one step further to get a

can be iterated one step further to get a  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class while

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class while  cannot.

cannot.

Proof: Constructing  is very similar to what we have already done. The easiest way to go about it is to first find

is very similar to what we have already done. The easiest way to go about it is to first find  a

a  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class for

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class for  by essentially the same argument as above. Then, restrict

by essentially the same argument as above. Then, restrict  to the first stage to get a

to the first stage to get a  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class  , i.e. an inductive full satisfaction class.

, i.e. an inductive full satisfaction class.

To construct  yet again apply the same argument from above. To ensure that it cannot be iterated further to produce an inductive

yet again apply the same argument from above. To ensure that it cannot be iterated further to produce an inductive  -iterated full satisfaction class, it suffices to work with a theory

-iterated full satisfaction class, it suffices to work with a theory  which is incompatible with

which is incompatible with  . This can be done because, by a version of Tarski’s theorem on the undefinability of truth,

. This can be done because, by a version of Tarski’s theorem on the undefinability of truth,  is independent over

is independent over  . This gives us

. This gives us  which cannot be extended to a model of

which cannot be extended to a model of  . ∎

. ∎

This gives us that the length a full satisfaction class be iterated to produce inductive iterated full satisfaction classes is not invariant under choice of satisfaction class. We can push this a little bit further and get that the length can be anything we desire.

WordPress is telling me that I’m nearly at two thousand words, so let me skimp on details. Similar to how we can write down a theory  for having a

for having a  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class, we can do the same for any

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class, we can do the same for any  and get

and get  . Indeed, if we work over a fixed

. Indeed, if we work over a fixed  we can talk about

we can talk about  for any

for any  . We also get

. We also get  , the theorems of

, the theorems of  in the language of arithmetic. By considering a theory

in the language of arithmetic. By considering a theory  extending

extending  but incompatible with

but incompatible with  we can get

we can get  , an

, an  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class which cannot be iterated any further. Therefore, any possible length can be achieved.

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class which cannot be iterated any further. Therefore, any possible length can be achieved.

Proposition: Let  be countable and recursively saturated and fix

be countable and recursively saturated and fix  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  . Then, for any

. Then, for any  in

in  , there is

, there is  so that

so that  but

but  cannot be iterated one step further to an

cannot be iterated one step further to an  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class. ∎

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class. ∎

This completely determines what can happen for iterated inductive full satisfaction classes of  -finite length. But, at least in some circumstances, we can go further. For instance,

-finite length. But, at least in some circumstances, we can go further. For instance,  proves the existence of iterated truth predicates of transfinite length. (Naturally, any

proves the existence of iterated truth predicates of transfinite length. (Naturally, any  in the second-order part of a model of

in the second-order part of a model of  must be inductive over the first-order part.) Thus, starting with a model

must be inductive over the first-order part.) Thus, starting with a model  of

of  we can find, say,

we can find, say,  which is an

which is an  -iterated inductive full satisfaction class for

-iterated inductive full satisfaction class for  . What can be said in general about iterated inductive full satisfaction classes of transfinite length?

. What can be said in general about iterated inductive full satisfaction classes of transfinite length?

proves that sufficiently nice (i.e. pretame) class forcings satisfy the forcing theorem—that is, these forcing relations

admit forcing relations

satisfying the recursive definition of the forcing relation. It follows that statements true in the corresponding forcing extensions are forced and forced statements are true. But there are class forcings for which having their forcing relation exceeds

in consistency strength. So

does not prove the forcing theorem for all class forcings. This is in contrast to the well-known case of set forcing, where

proves the forcing theorem for all set forcings. On the other hand, stronger second-order set theories such as Kelley–Morse set theory

prove the forcing theorem for all class forcings, providing an upper bound. What is the exact strength of the class forcing theorem?

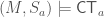

, the forcing theorem for all class forcings is equivalent to

the principle of elementary transfinite recursion for recursions of height

. This is equivalent to the existence of

-iterated truth predicates for first-order truth relative to any class parameter; which is in turn equivalent to the existence of truth predicates for the infinitary languages

allowing any class parameter

. This situates the class forcing theorem precisely in the hierarchy of theories between

and

.